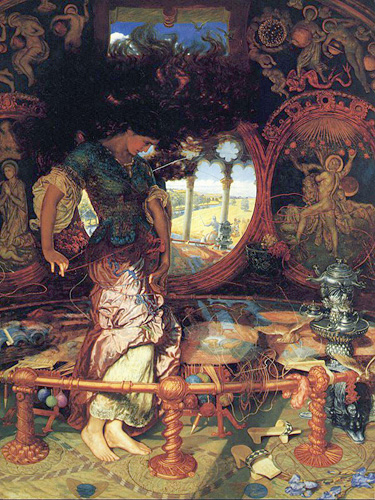

William Holman Hunt – The Lady of Shalott (1905)

This painting was begun in 1886 and finally exhibited in 1905. Today, it hangs in the Manchester Art Gallery.

The story of The Lady of Shalott is described in the eponymous poem by Tennyson. It is largely inspired by the tale of Elaine of Astolat, related in Thomas Malory’s famous 15th-century work Le Morte d’Arthur, though Tennyson himself claimed the primary influence was a 13th-century Italian novelette entitled Donna di Scalotta.

Elaine of Astolat is a fair maiden who falls in love with the great knight Lancelot but dies of a broken heart when she realises her love will never be requited. She leaves instructions for her body to be placed in a black barge. One of her hands clutches her favourite flower – the lily – while the other clasps her last letter. The barge floats down the Thames to Camelot where it is discovered by members of Arthur’s court. They read Elaine’s letter to Lancelot, who then explains what took place between the maiden and him. He pays for a grand funeral for her.

In Tennyson’s poem, there is no physical contact between The Lady of Shalott and Lancelot. The Lady lives under a curse, the origin of which is never revealed, and is condemned to spend her days in an isolated fortress tower on an island in the middle of a river. Day and night, she weaves a magic web, full of brilliant colours. She is permitted to look at the outside world only via its reflection in a mirror. However, one day she glimpses Lancelot riding past and is so smitten she cannot resist looking at him directly. Instantly, her mirror shatters, her web is destroyed, and the curse’s punishment falls on her. She leaves the tower, and sets out downriver for Camelot in a small boat. She sings a final song and then she dies. Her boat reaches Camelot where Arthur’s knights find it. Lancelot, who has never cast eyes on her before, says she has a lovely face.

Tennyson’s poem has poweful allegorical and metaphorical resonances. It might, given Victorian mores, be said to represent the disaster that would befall an unmarried woman if she surrendered to sexual temptation. In a sense, her life was over, especially if she fell pregnant.

It might describe the gnostic idea that souls in spiritual heaven (represented by the pure Lady in her tower) can become enamoured of the material world (represented by Lancelot and Camelot) and succumb to the lure of earthly delights with dire consequences. The souls then become trapped in the physical world, symbolising the death of spirituality.

The poem might symbolise the struggle of a shy, sensitive person to find a place in a brash, uncaring world. (The Lady of Shalott writes her name on her boat – a futile attempt to establish her identity in the ‘real’ world. Lancelot, the object of her passion, has no idea who she is – the indifference of the ‘real’ world.)

By a similar token, the poem can represent the ordeal of outsiders who try to fit in. They have a tremendous desire for normality, to be no longer persecuted and reviled, but when they enter the normal world, they fail to engage with it. In their despair, they may take their own lives.

The river down which the Lady floats may be the river of life, its currents too strong for sensitive beings, causing them to drift away into oblivion and death.

Another possibility is that the poem encapsulates the dilemma facing artists. To find the time and space to pursue their work (to weave their webs), they need to cut themselves off from ordinary life (to look, so to speak, obliquely rather than directly at the world; represented by looking at the world via a mirror). They may well become isolated and reclusive. In time, they may regard this lonely artistic existence as a curse and choose to plunge into ‘normal’ life, thus sacrificing their gift (the sacrifice being symbolised by The Lady of Shalott’s death), and they may fail in any case to establish a home and identity in the alien and hostile non-artistic world.

In a similar vein, the tale may represent the academics in their ivory towers who study the ordinary world yet find it difficult to gain acceptance in that world. Their talents are simply not valued there, and they’re doomed if they go there.

In his painting, Hunt chooses to depict the pivotal moment when the mirror cracks and The Lady of Shalott knows the curse has been activated. (The other logical part of the tale to illustrate is the Lady’s tragic journey to Camelot. Here, John William Waterhouse’s famous 1888 painting provides the definitive image.)

Hunt is alive to the complex symbolism the poem offers. He may have seen it as reflecting his own position regarding art. The artist’s duty is to resist the blandishments of the world and remain true to his art, with his artistic integrity retained. To do anything else is to court disaster, as exemplified by the fate of The Lady of Shalott – herself an artist – who surrendered to temptation.

What are the main features we can discern in the painting? Hunt himself provides a detailed exegesis in his 1905 catalogue entry for this painting:

1. Tennyson, in the poem of ‘The Lady of Shalott’, deals with a romantic story which conveys an eternal truth, based on the romance of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. The name of the Lady and the events recorded are the invention of the poet.

2. The progressive stages of circumstance in the poem are reached in such enchanting fashion as to veil for the casual reader the severer philosophic purport of the symbolism throughout the verse.

3. The parable, as interpreted in this painting, illustrates the failure of a human soul towards its accepted responsibility. The lady typifying the Soul is bound to represent faithfully the workings of the high purpose of King Arthur’s rule. She is to weave her record, not as one who, mixing in the world, is tempted by egoistic weakness, but as a being ‘sitting alone’; in her isolation she is charged to see life with a mind supreme and elevated in judgement. In executing her design on the tapestry she records not the external incidents of common lives, but the present condition of King Arthur’s Court, with its opposing influences of good and evil. It may be seen he is represented on his double throne, the Queen is not there, and he is saddened by her default; but he is still supported on his right and his left by the virtues.

4. At his right hand Charity is sheltering motherless children under her aegis, while justice and Truth are on his left.

5. The knights below are bringing their services. Sir Galahad is offering on his shield the cup of the Holy Grail, which alone pure innocence and faithfulness have enabled him to attain; parts of the web which are not yet completed would reveal the true services of other knights, but on the left of the embroidery the Lady has already pictured the vainglorious Sir Lancelot, who brings no offering but lip-service, kissing his finger tips.

6. The Lady’s chamber is decorated with illustrations of devotion of different orders: on one hand the humility of the Virgin and her Child, and on the other the valour of Heracles who, having overcome the dragon, is seizing the fruit of the garden of the Hesperides while the guardian daughters of Erebus are dead in sleep.

7. The mirror stands as the immaculate plane of the Lady’s own inspired mind, or, if you prefer the interpretation, the unsullied plane upon which Art should reflect Nature as opposed to bald realism, and so far she has obeyed, but seeing the happiness of the common children of men denied to her for the time wavering in her Ideal she becomes envious, and cries, ‘I am half sick of shadows’.

8. In this mood she casts aside duty to her spiritual self, and at this ill-fated moment Sir Lancelot comes riding by heedlessly singing on his way.

9. Fascinated by his reflection in the mirror, she turns aside to view him through the forbidden window opening on to the world below.

10. Having forfeited the blessing due to unswerving loyalty, destruction and confusion have over-taken her. The mirror ‘cracks from side to side’, the doves of peace which have nested in her tower find refuge from turmoil in the pure ether of the sky, and in their going extinguish the lamp that stood ever lighted, her work is ruined; her artistic life has come to an end. What other responsibilities remain for her are not for this service; that is a thing of the past. It was suggested to me that the fate of the Lady was too pitiful! I had Pandora’s Box with Hope lying hid, carved upon the frame.

11. Unwittingly, the traitor Lancelot, imparts consolation in his final words -- She has a lovely face; God in His mercy lend her grace, The Lady of Shalott.

To what extent does Hunt faithfully reflect the story? Certainly, all the main ingredients of the critical moment are portrayed, but he adds many symbolic elements missing in the source material (Hercules, the Virgin Mary, the lamp, the doves, the wild hair etc).

This is a good example of how a story mutates, gaining new features, a new ‘spin’. Although Hunt would seem to have captured a truth suggested by Tennyson’s poem, has he done proper service to thetruth of the poem? Is there even such a thing as a definitive truth of any artistic work? Perhaps truth, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder, and as each new person comes to an artwork, they will find their own way to interpret it. Through this mechanism, all stories, myths and legends evolve as they are continually reinterpreted, embellished and ‘improved’.

Interestingly, Hunt met Tennyson, and they discussed an earlier version of Hunt’s depiction of The Lady of Shalott. Hunt recollected their conversation:

‘Why did you make the Lady of Shalott, in the illustration, with her hair wildly tossed about as if by a tornado?’

Rather perplexed, I replied that I had purposed to indicate the extra natural character of the curse that had fallen upon her disobedience by reversing the ordinary peace of the room and of the lady herself; that while she recognised that the moment of the catastrophe had come, the spectator might also understand it.

‘But I didn’t say her hair was blown about like that. Then there is another question I want to ask you. Why did you make the web wind round her like the threads of a cocoon?’

‘Now,’ I exclaimed, ‘surely that may be justified, for you say -

‘Out flew the web and floated wide!’

Tennyson insisted, ‘But I did not say it floated round and round her.’ My defence was, ‘May I not urge that I had only half a page on which to convey the impression of weird fate, whereas you had about fifteen pages to give expression to the complete idea?’ But Tennyson laid it down that ‘an illustrator ought never to add anything to what he finds in the text.’

Here we see how The Lady of Shalott no longer ‘belongs’ to her creator. Tennyson objects to Hunt’s interpretation, yet Hunt seems justified in his choices. The problem, of course, is that all artworks contain multiple subtexts, some of which may not have been consciously intended by their creators, and it’s often these shadowy subtexts rather than the primary text which influence other artists.

Whereas Tennyson appears to view The Lady of Shalott as a largely tragic and romantic figure, the hapless victim of a curse, Hunt sees her as an active participant in her downfall. She chooses to be ruined. She courts and merits the curse. She is a fallen woman rather than a falling woman.

In his dramatic depiction of The Lady of Shalott, Hunt invokes the Victorian conventions for depicting prostitutes or adulteresses. The trajectory of the archetypal Victorian fallen woman is initial innocence followed by seduction and abandonment, culminating in the woman becoming an outcast. Her despair and remorse frequently conclude in suicide. All of these elements are explicitly or metaphorically present in The Lady of Shalott’s sad tale.

Hunt shows the Lady’s sexual awakening by depicting her with bare arms and tousled hair. Victorian iconography required the fallen woman to be represented in gaudy, over-elaborate terms to illustrate her descent from natural simplicity. Hunt’s Lady is clearly not dressed or posed as a simple maid; she wears the finery of a courtesan. Although she has not literally been sexually corrupted, her ideological innocence is metaphorically violated, thus the analogy with the fallen woman.

Hunt seems to be asserting that he and not Tennyson has discovered the eternal truth contained in the tale of The Lady of Shalott. That may or may not be the case, but Hunt has certainly produced a startling work of art that deepens our engagement with Tennyson’s haunting poem.